Archetypes of Resilience: Reinventing Traditions Through Icons, Religions and Prints

- Coronado Print Studio

- Jul 10, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 22, 2023

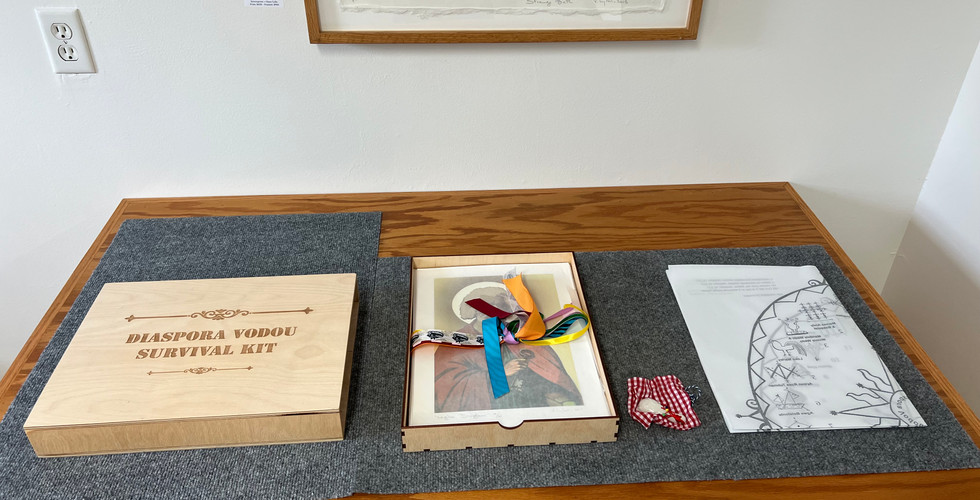

Coronado Print Room, Coronado printstudio’s gallery space is currently showing the solo exhibition, Pantéon: When the Saints Go Marching! by Vladimir Cybil Charlier. Premiering at the studio, Cybil’s most recent portfolio, titled Diaspora Vodou Survival Kit comprises an edition of 22 prints, as well as a table of content poster and a limited edition porcelain sculpture encapsulated in a handmade wooden box. This exhibition also highlights previous prints Cybil has published at Coronado printstudio, such as her screenprint, A Strange Bath, which aims to address the border conflict and political tension between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and “Rose” All Language is a Longing for Home: an intimate portfolio of mixed-media linocuts depicting delicate symbology that explores the sacred African creation myth of Thezain.

An insight into the establishment of the island of Hispaniola or Quisqueya, and understanding of the historical context behind Cybil’s Survival Kit makes it easier to fully appreciate the nuanced content of these series. During the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th-19th centuries, enslaved West Africans were forbidden from practicing their traditional religions and forced to convert to Catholicism by the French colonists. In order to continue practicing their religions without risking their safety, these new communities co-opted the Christian visual lexicon by reinterpreting it along their pre-existing religious traditions.

Using predominantly catholic images as decoys, the diasporic religion of Vodou emerged in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which later became the Republic of Haiti. For example, Saint Peter, the doorkeeper of heaven who is often depicted holding keys in traditional Roman Catholic imagery, is typically associated with Papa Legba because he is understood to be the “key” to the spirit world, the guardian of the “gates” to the other realm.

Saint Peter by Marco Zoppo (right) and Papa Legba by turpentyne (left).

This aggregation of beliefs demonstrated the ingenuity of the local population to evolve and

adapt in the face of adversity. It also highlighted their strong desire for agency and refusal to

conform to oppressive forces. This resilience ultimately led Haitians to rebel against their

oppressors and become the first black republic to gain independence in the world. In this portfolio, Cybil continues this diasporic narrative by integrating new-world icons that

have played an integral role in the development of the diasporas now established in the United States. By incorporating modern he/she-roes into traditional iconography, Cybil bridges the legacies of the original African diaspora and its descendants, thus examining how traditions reinvent themselves. In addition to this, she also bestows a degree of holiness on exemplary individuals from the African-American and Latinx communities, perhaps to honor their advances in the arts and social activism in the Americas.

Example of vèvès. Photo credit: Deterville, D. (2019, May 29). Drawing down spirits: Sacred ground markings of Vodou in San Francisco. Open Space. Website link here.

Cybil embarked on thorough research to accurately reinvent these traditional entities without disregarding the sophisticated and complex system established in the Vodou religion. As such, she preserved its ritualistic factor by recreating vèvès in the portfolio's poster, which are individualized symbols created with flour or cornmeal on the floor of the ceremonial space during rituals to summon specific spirits, also known as lwas.

Each lwa has its own personality and is associated with specific colors and objects. Cybil also creates associations between the lwas and their modern equivalents, like Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul, embodying Gran’ Brijit, goddess of the underworld.

Selection of prints from Vladimir Cybil Charlier's Diaspora Vodou Survival Kit (from left to right): Frederick Douglass as Papa Legba; Aretha Franklin as Gran’ Brijit, and James Baldwin as Ti Jean Dantor.

ON PRINTMAKING AS THE MEDIUM OF CHOICE

Initially, one of the primary purposes of printmaking was to produce religious imagery to

educate dominantly illiterate populations about the word of God. The nature of the multiplicity of printmaking made it more affordable for the working class to access and easier to disperse their message. Cybil explains that it was a natural decision to opt for printmaking as the medium of choice for this portfolio due to the legacy and purpose of religious iconography in society, posing a great argument when speaking of the value of printmaking itself.

Traditionally, master printers either illustrated passages of the bible or replicated mass-produced paintings as etchings and woodcuts. However, with more technological advances,

new, more accessible, and cheaper ways to reproduce works of art, such as digital printing, came at hand.

The Last Judgment fresco by Michelangelo covering the whole altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City (right), and engraving reproduction by Martino Rota (left).

While the value of an image tends to decrease through editioning, Cybil argues this notion with The Pantéon by begging the question, how can the value of an image decrease due to being reproduced when its very intention is to be disseminated?

Culture does not lie in the grounds of a building, nor is it contained within country borders. It is carried by the people and transformed by the environments they encounter. The existence of Vodou or Santeria, and Lucumi or Candomble as religions is a clear example of this fact. After being stripped from their lands, families, and freedom, preserving their religious beliefs was a way for enslaved people to affirm their identities and cope with the unforgiving conditions and atrocities they faced during slavery.

When communities face disruptive events, such as wars or mass immigration (whether forced or voluntary), any symbol its people abandoned is as good as gone, thus making any artwork whose values rely on its exclusivity obsolete. Through prints, generations can continue carrying their culture because it’s an art that will always be within reach of their communities.

As noted in Cybil’s biography, her work is continuously informed by her experience growing up between New York City and Port-au-Prince. As an American of Haitian descent, she encounters a new syncretism of cultures created by her diaspora experience, the values she reinvented, and the ones she cherished.

Homemade Vodou altar. Photo credit: Art Encountered.

When looking at Cybil’s work, we see the tension in the story of an American and an immigrant, the history of a culture, and the continuation of a legacy. Her work examines spectrums of cultural margins, like past and present, here and there, and the complexities found within and between them.

Written by Palén Obesa, Coronado printstudio’s Collection Manager.

Comments